The state’s “black belt” made big turnout gains in support of the Democratic candidate, providing his margin of victory in the Senate special election in a deep red state.

Six of 10 black voters stopped by a New York Times reporter in a shopping center last week didn’t know an election was even going on, a result the reporter took to mean overall interest was low. The Washington Post determined that black votersweren’t “energized.” HuffPost concluded that black voters weren’t “inspired.”

If Democratic candidate Doug Jones lost to GOP candidate Roy Moore, weakened as he was by a sea of allegations of sexual assault and harassment, then some of the blame seemed likely to be placed on black turnout.

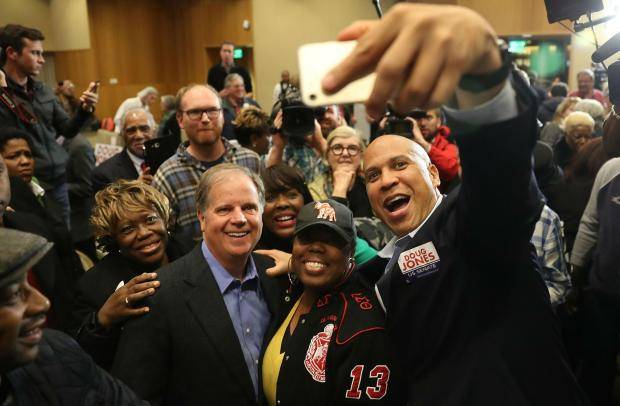

But Jones won, according to the AP, and that script has been flipped on its head. Election day defied the narrative, and challenged traditional thinking about racial turnout in off-year elections and special elections. Precincts in the state’s “black belt,” the swathe of dark, fertile soil where the African American population is concentrated, reported long lines throughout the day, and as the night waned and red counties dominated by rural white voters continued to report disappointing results for Moore, votes surged in from urban areas and the black belt. By all accounts, black turnout exceeded expectations, perhaps even passing previous off-year results. Energy was not a problem.

Exit polls showed that black voters overall made a big splash. The Washington Post’s exit polls indicated that black voters would make up 28 percent of the voters, greater than their 26 percent share of the population, which would be a dramatic turnaround from previous statewide special elections in the South, including a special election for the Sixth District in Georgia which saw black support for Democratic candidate Jon Ossoff dissipate on Election Day.

Meanwhile, Moore’s support sagged in mostly white counties. The race was probably over for the former state chief justice when Cullman County, which is virtually all white and heavily supported Trump in 2016, only turned out at 56 percent of its 2016 levels. It really does seem that although many white voters weren’t convinced to vote for Jones, the allegations against Moore persuaded many of them to stay home.

These results demolish the pre-established media narrative about black voters in the state, and defy conventional wisdom. Black voters were informed and mobilized to go vote, and did so even in the face of significant barriers.

The grassroots organizing in black communities by groups like local NAACP chapters was more muscular than it had even been in the 2016 general election. In the lead-up to Tuesday’s contest, voting-rights groups registered people with felonies, targeted awareness campaigns at people who might not have had proper ID, and focused specifically on knocking down the structures in place that keep black voters away from the polls. Their efforts immediately become a case study in how to do so in a region that has, since the Supreme Court’s 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision curtailing the 1965 Voting Rights Act, become a bastion of new voter-suppression laws, including new voter-ID laws.

The prospects of those laws and efforts to circumvent them will be further tested in the 2018 elections. But, for now, Jones is the man in Alabama, and even as white voters by and large stuck with Moore, Democrats were saved by a community already fighting against the grain to be heard in the din of democracy.