BY JERRY BEMBRY

Nick Blakely brightened every room he entered, and that was certainly the case as he strolled into his first international business class in the Lynn Business Center on the campus of Stetson University.

Blakely had, on this last Monday of August, many reasons to feel euphoric. In five days the sophomore would make his college football debut as a backup linebacker for the Stetson football team, fulfilling a dream he had from the first time he put on a pair of pads as a 6-year-old: a chance to play Division I football.

The Stetson coaches loved Blakely’s braggadocian nature, and they enjoyed the extra smack talk in the weight room and those extra licks he’d deliver in practice that pushed his teammates to maximum effort. They liked it so much that Stetson head coach Roger Hughes grabbed Blakely by the arm when he encountered him not long before that Aug. 28 class to deliver a message.

“Nick, do you know how good you can really be?” Hughes asked him. “If you get your head on right, you can be really good.”

“Thanks, Coach,” was Blakely’s brief reply.

When Blakely entered that international business class, he took a seat in the middle of three rows. Since it was opening session of the semester, the professor decided to begin the class with a go-to icebreaker:

“Introduce yourselves, name your favorite place you’ve ever been,” she told the students, “and tell us the one place you’d like to visit.”

The responses were typical of college students as they named a series of beaches or exotic destinations. Patrick Farley, a fellow football player seated just to the right of Blakely, shared that the best place he had visited was London, and the place he most wanted to explore was Japan.

When it was Blakely’s turn he — ever the jokester — said the best place he’d ever been was the Cheesecake Factory, leaving his classmates doubled over in laughter.

Then came the place he’d most like to visit, and Blakely, who grew up in Lawrenceville, Georgia, paused for a moment to think.

“I’m not much of a traveler,” he said. “But I would sure love to go to heaven one day.”

Just hours later, during what coaches and teammates described as a light practice, Blakely complained of dizziness. He was pulled aside to rest and seemed to be improving as he was being monitored by a trainer. At some point he attempted to stand up, and collapsed.

Blakely was rushed by ambulance to Florida Hospital DeLand, where he died of sudden cardiac arrest (SCA), less than 2 miles from campus.

His friends claim you never saw Nick Blakely without a smile. And if he wasn’t smiling, he at least had a grin.

STETSON UNIVERSITY

That’s backed up by his team photo on the Stetson website, and most every picture you’ll find of him on social media.

Often, that cheery demeanor was misconstrued. Like the time coach Jamal Page glanced over at Blakely while delivering one of those fiery, about-to-pop-a-blood-vessel speeches to his 9-year-old youth football team. Every face he glanced at as he scanned the room returned an intense glare. Except when his eyes landed on Blakely, who smiled as he bit down on his mouthpiece.

Page erupted. “Why are you always smiling,” he screamed, slowly and deliberately, as he scowled at Blakely.

Blakely never blinked, and continued to smile. And chomp.

Blakely was a slightly chunky kid back then and the coaches, obviously, wanted him to play on the line. In most games he’d line up at center, but he wanted the glory of the kids in the backfield that he helped spring for big runs.

EVEY WILSON FOR THE UNDEFEATED

He asked his mother why he couldn’t run with the ball, and she said, honestly, that he wasn’t small enough.

“OK, mother,” Blakely told her. “You just watch and see.”

A preteen Blakely dedicated himself to training, asking a friend’s dad to help him transform his body.

As his body got leaner, his responsibilities on the football field expanded. By 13, Blakely was playing running back and linebacker.

Blakely’s newly fit body was Instagram-ready, and he didn’t hesitate to put it on display. A large part of his teenage years was spent shirtless.

“It would be winter and we’d have one of those rare 20-degree days and he’d take out the trash with no shirt,” said Israel Soto, one of Blakely’s neighbors. “I’d joke with him, ‘You know they test you for that stuff, right?’ And all he’d do was laugh.”

Blakely was buff. And bold enough to walk up to his friends’ mothers for them to rub lotion on his back (they’d oblige).

Blakely was deeply religious. He’d quote Scriptures and discussed God and religion in a way that didn’t turn his friends off. “He loved God, and he would sit at the dining table pondering life and heaven,” said Babette Wallace, a next-door neighbor. “At times he would challenge the Bible. I credit Nick with bringing my son closer to God.”

Blakely possessed a kind soul. During his free period at Archer High School he’d often visit the special education class to spend time with the students. “Sometimes he’d take them outside to throw a football around, and they loved that,” said Esther Andrade, who worked with the special ed students at Archer. “Those kids thought the world of football players, so they enjoyed the time he spent with them.”

Blakely hugged most people he encountered and often parted ways by telling friends that he loved them — both men and women. “Who does that?” said Monica Jones, the mother of his good friend Brandon Jones. “But Nick was different.”

Blakely was loved by the girls. Madison Bowler, who’s two years younger than Blakely, was once left swooning after seeing Blakely, by that time in high school, at a mall.

“Mom, he’s breathtaking,” she said.

“Yes, he is,” was her mom’s response.

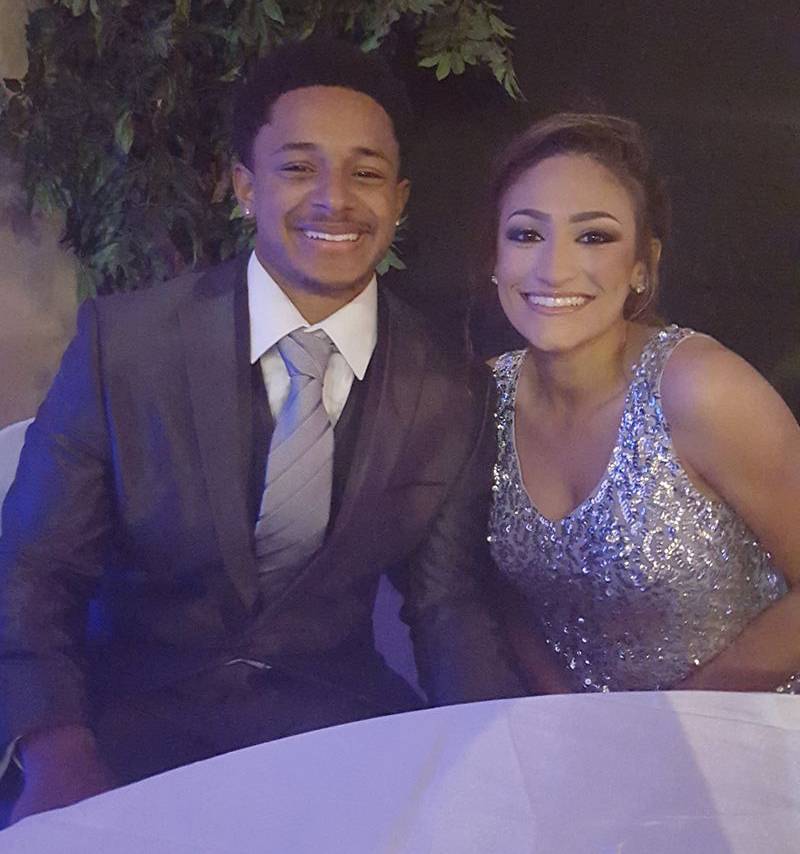

That’s kind of the reaction Jacqui Switzer had when she first saw Blakely in a middle school basketball game. Switzer played girls’ basketball at a rival school and hung around to watch the boys play. Her friend asked if she liked one of the boys on the opposing team.

“No, but I like that No. 21.”

COURTESY OF MICHELLE FIELDS-WILSON

Switzer, who plays softball at Florida, had all but forgotten No. 21 until she got to Archer. She spotted her middle school crush in the hall and discovered that they had the same lunch period. Eventually, the two started dating and stayed together until late in their senior year.

Blakely was also a fierce competitor in everything he did. He’d get upset if he lost playing video games. If you beat him in cards, he’d demand a rematch and would play until he won.

That competitiveness carried over to the football field as well. Blakely played a big role as a junior on a team that lost in the Georgia State 6A championship game, and he was the starting linebacker as a senior on the Archer team that made a deep run in the state playoffs.

“He make a play he’d come to the sidelines with a big smile,” said Archer coach Andy Dyer. “He was a strong kid who was built to play football.”

A good player at a small-town high school doesn’t always equal big-time Division I opportunities. Major programs weren’t rushing to Archer to dangle scholarships. Blakely did get offers from Stetson and Georgia State, both D-I schools in the FCS.

When he signed his letter of intent to play at Stetson on signing day — his good friend and high school teammate, Jeremiah Nails, had earlier accepted a scholarship there — Blakely moved one step toward realizing his dream of playing Division I football.

As Blakely began his Aug. 28 practice, his mother was home in Georgia settling in for the evening. Fields-Wilson would occasionally go to the Stetson practice feed on her computer and try her best to find Blakely’s No. 37 jersey.

EVEY WILSON FOR THE UNDEFEATED

On this particular night she was taking care of a few last chores so she could watch the TV One original film that was titled, ironically, When Love Kills: The Falicia Blakely Story.

Then Fields-Wilson’s phone rang.

It was coach Hughes.

“Nick had a seizure.”

“Nick had a seizure?” she replied. “Tell him to get up.”

It wasn’t that simple, she was told. The ambulance was already at the field and was about to take him to the hospital.

Fields-Wilson began to panic. She quickly booked a flight from Atlanta to Orlando, Florida, and hustled upstairs to throw a few items in a travel bag. She called a few friends, telling them what had happened. “I’ve got to get to Nick, I’ve got to get to Nick …,” she kept repeating to herself.

By the time she was loading the car, a doctor at the hospital called and told her that Blakely had suffered cardiac arrest.

A short time later, the doctor called back.

“Your son’s gone.”

Fields-Wilson collapsed in the street. Her next-door neighbor, Wallace, was already by her side, and within minutes, news of Blakely’s death quickly spread.

Brandon Jones was in his dorm room at Albany State when a friend called with the news. In disbelief, he called his mother, Monica Jones, who had received a call from Fields-Wilson earlier. “As soon as she started crying, I knew it was real.”

Andy Dyer, Blakely’s coach at Archer, had put his cellphone away for the night when his son brought it to his room after it kept ringing continuously. “Dad, somebody keeps calling you and calling you.”

Page, who coached Blakely’s rec league football team, was at practice when a friend called and asked him to sit down before he broke the news. “It hit me that I wouldn’t be able to say goodbye, I wouldn’t be able to tell him I love him, and I wouldn’t be able to tell him that I’m proud,” Page said, getting emotional. “Gone well before his time.”

Within minutes, the cul-de-sac where Fields-Wilson’s house sits on the edge was filled with cars. An entire community of family, friends, football moms and former teammates rushed to Fields-Wilson’s side as she grieved outside her home.

It was the exact place where she had last seen her son just weeks earlier as he prepared to return to school.

As Nick loaded his car to drive to Florida, Fields-Wilson grabbed her son by the arms and looked him in his eyes.

“I am so proud of you,” she told him. “I know this is going to be a good year for you. Just do your best and be your best.”

The two prayed. Blakely hugged his mother and told her that he loved her.

“I love you.”

“I love you too, mother.”

Then he drove off.

Two weeks later, Blakely was dead. More than two months after her son collapsed, Fields-Wilson remains in shock.

“I wake up every day knowing that he’s not coming through that door,” Fields-Wilson said. “That’s hard for me.”

EVEY WILSON FOR THE UNDEFEATED

Just weeks after Blakely’s death, Kenia Soto sat in the stands at Archer High School watching her son, Edwin, make his debut on the ninth-grade team. For years, Soto, Wilson’s neighbor, had watched her son’s games with no worries.

This time was different.

“Hardest game I ever watched in my life,” said Soto. “I just kept thinking about this healthy, physically fit kid leaving like that, and it made me fearful. If my son never plays football again, I’d be OK with it.”

The cause of Blakely’s death, sudden cardiac arrest, is not uncommon.

- Dominick Bess, a 14-year-old junior varsity player in New York City, collapsed during practice and died less than a week before Blakely.

- Eight-year-old Jaiden Jones collapsed at one of his September football practices in Elizabeth City, North Carolina. The cause: a heart anomaly.

- Loyola Marymount college basketball star Hank Gathers collapsed during a March 4, 1990, West Coast Conference tournament game against Portland, just moments after catching an alley-oop pass from half court. He was carted off the court on a stretcher with his shocked family by his side. He died at the hospital, and an autopsy revealed a heart muscle disorder. He had previously been diagnosed with an irregular heartbeat after collapsing during a home game in December.

- Boston Celtics All-Star Reggie Lewis was 27 when he died of a heart ailment during an off-season workout in 1993, just four months after collapsing during a first-round playoff game.

Just last weekend, South Carolina State guard Tyvoris Solomon had to be revived after collapsing on the team’s bench in a game at North Carolina State.

SCA is the No. 1 killer of student-athletes and the No. 2 medical cause of death for people under age 25. According to the American Heart Association, 1 in 3 youths has an undetected heart condition that puts them at risk of SCA. A 2016 report commissioned by the NCAA revealed that 1 in 5,200 African-American men is at risk.

An electrocardiogram (EKG) test, which measures electrical activity in the heart, can detect those hidden heart conditions. That’s what happened in September when Jaylen Brantley, who was about to play his final season of college basketball at Massachusetts, found out after an EKG that his heart muscles were abnormally large.

The exam that saved his life was required by UMass, the alma mater of Reggie Lewis. But not every school requires an EKG.

It almost happened: The chief medical officer of the NCAA recommended in 2015 that all male athletes be given EKGs. But he changed his mind after nearly 100 member schools questioned the use of the screening because of false positive results.

Fields-Wilson doesn’t want another parent to experience the suffering she’s endured since her son’s death. Which is why she launched Smiling Hearts: The Nick Blakely Foundation, which she hopes will promote awareness of SCA.

EVEY WILSON FOR THE UNDEFEATED

“We want to increase recognition of this problem,” Fields-Wilson said. “We want to take this to school and to youth sports organizations to let everyone know that this is a serious problem.”

Fields-Wilson has had numerous conversations with Georgia state Rep. Joyce Chandler since Blakely’s death and hopes to introduce a bill in January that would require athletes who collapse during games or practices to get medical clearance before they’re allowed to return.

“We’re hoping to have testing of athletes in the high school during the spring,” Wilson said. “I just want to do my best to not let Nick have died in vain.”

Blakely’s shocking death has already reached many residents in Lawrenceville. Blakely’s older sister, Paige, has already taken her 8-year-old daughter to the doctor for extensive tests for her heart.

Page, who coached Blakely’s youth football team, is urging all of his players’ parents to test their kids beyond the normal physical.

“I tell these parents the story about Nick, and how he was strong as a horse,” Page said. “And I tell them that even though their kids are 9, they should go that extra mile. If your kid is playing any sport, you should have your child’s heart screened at least every three years.”

It’s the morning of Nov. 4, and Fields-Wilson’s up early to attend a women’s prayer service with her mother and sister at church. Then it’s back home for a moment to reflect before pulling on her T-shirt with “Stetson Hatters Mom” on the front and Blakely’s name and uniform number, 37, on the back.

The original plans for this day, which would have been Blakely’s 20th birthday, were thought out long in advance. From the moment the Stetson schedule was released, Fields-Wilson had planned to be in Florida to attend Stetson’s home game against Butler.

She’d watch the game in the stands with the other Stetson moms whom she had bonded with closely. After the game there would a celebration dinner — perhaps even at Blakely’s favorite place to visit, the Cheesecake Factory, which was less than an hour’s drive south of DeLand in Orlando.

Fields-Wilson, instead, loaded a couple of dozen red and white balloons in the back of her SUV and made the 15-minute drive to Gwinnett Memorial Park, where Blakely is buried.

She had invited a few people, but Fields-Wilson wasn’t sure how many would show. As she made a left turn and neared the section of the cemetery of Blakely’s grave, she got emotional as she saw the long line of cars that were parked at a place she visits two, three times a week.

“Oh, my goodness,” Fields-Wilson said, spotting the close to 20 cars parked and many more arriving. “This is awesome.”

All came with special memories of Blakely.

EVEY WILSON FOR THE UNDEFEATED

Kohen Hayes, a high school friend, remembered the kind young man who, when he came home on break, would call her and insist she attend church. “He was very spiritual and had a one-on-one connection with God,” Hayes said. “I think that’s one of the reasons why he was always so happy and so positive: because he knew, no matter what, that God would always be in his corner.”

Amy Majica recalled her son’s friend who, when he was 7, developed a crush. “He’d tell my son, ‘I’m going to marry your mom’ and look at me and say, ‘Right, Ms. Amy?’ ” she said, laughing before becoming emotional. “A lot of our kids are sophomores in college, and he’s not here right now.”

Brandon Jones remembers meeting Blakely during youth football team, when two rivals eventually developed a close bond. “I would call him all the time, or text him, and now I can’t do that anymore,” said Jones, a student at Albany State University, struggling to fight through tears. “We’re trying to overcome this. We’re trying to heal. But it’s just too hard.”

After letting the crowd gather for a few minutes on the side of the road, Fields-Wilson made sure everyone had a balloon and then led the group over to Blakely’s grave, where the grass still showed signs of the squared corner cuts of freshly laid sod that hadn’t had time to blend in with the surrounding grass — a telltale sign of a recently dug grave.

“Thank you so much,” Fields-Wilson said. “It means a lot to me for you to be here today to celebrate Nick’s life.”

There were few dry eyes as the group sang the traditional “Happy Birthday” song before releasing the balloons and chanting, “We love you, Nick.” At that moment one of the women shouted the opening chords of Stevie Wonder’s version of the song, resulting in rhythmic clapping and a soulful serenade that filled the air around Blakely’s grave marker.

The Lawrenceville community and beyond has rallied around Blakely’s family. His mother, father Milton Blakely, grandmother and siblings have received a show of support since Blakely’s death.

But the hard times since Blakely’s death become even more difficult with his recent birthday, Thanksgiving and the Christmas season.

“Before Nick died, I’d spend a lot of time watching football games on the weekends,” Fields-Wilson said. “I don’t even do that anymore. It’s going to take some time.”

Each year during the holidays, Blakely would invite family and a bunch of friends over for a marathon game night. It would be loud, it could get heated, and often Blakely was the one in the middle of the ruckus.

There will be no game night this holiday season. Not in Fields-Wilson’s house, but she knows her son will be playing.

“Nick’s very competitive, so I know he’s in heaven still competing,” Fields-Wilson said. “So I’m sure he’s in heaven playing cards.

“And if he’s losing,” she added. “I can see him saying, ‘OK, God, let’s play another.’ ”

Jerry Bembry is a senior writer at The Undefeated. His bucket list items include being serenaded by Lizz Wright, and watching the Knicks play an NBA game in June.