By Samantha Schmidt and Sandhya Somashekhar

“Definitely Puerto Rico — when we can get outside — we will find our island destroyed,” Puerto Rico’s emergency management director, Abner Gomez, said at a midday press conference, adding that 100 percent of the island is without electricity. “The information we have received is not encouraging. It’s a system that has destroyed everything it has had in its path.”

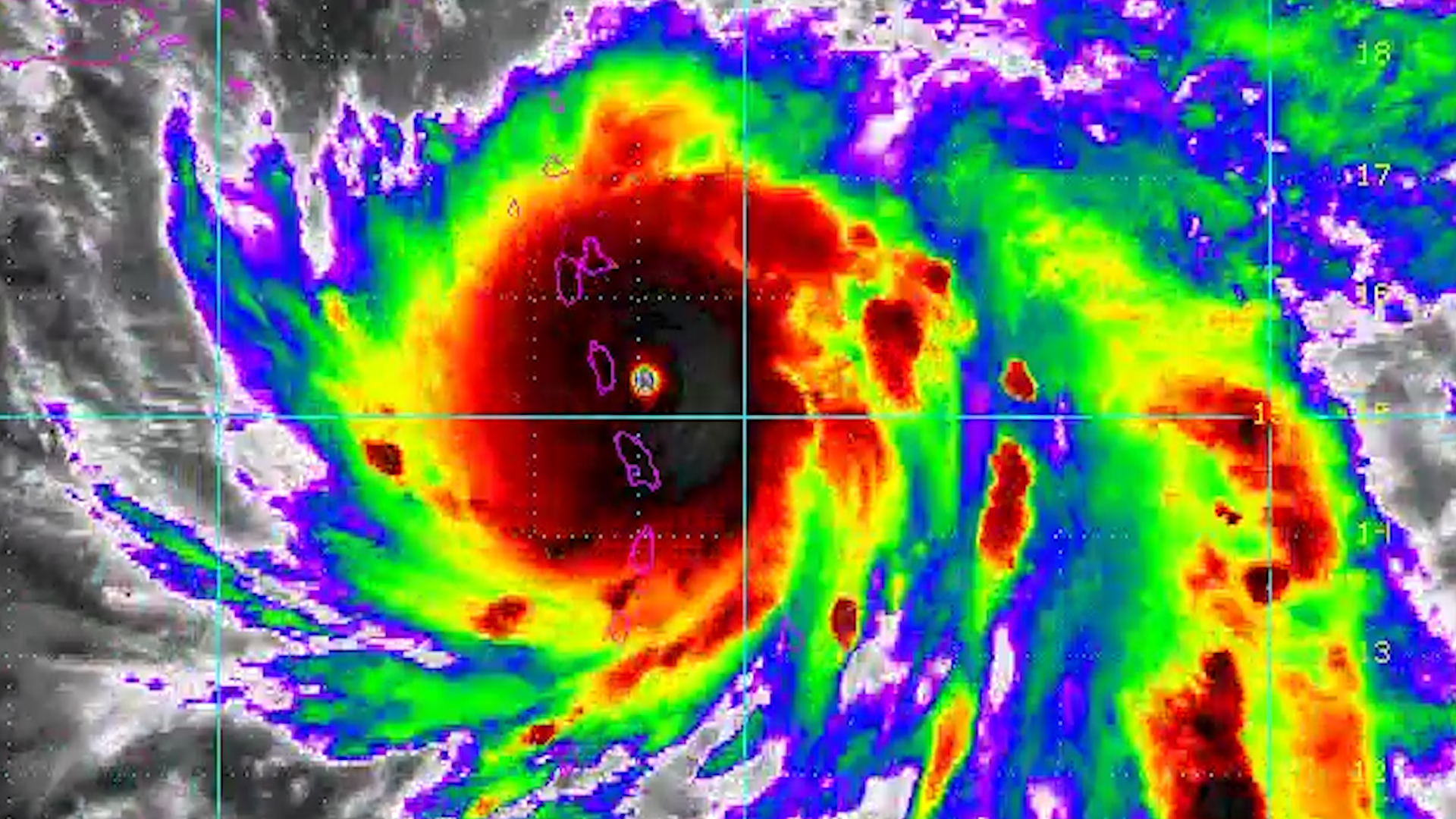

The storm first slammed the coast near Yabucoa at 6:15 a.m. as a Category 4 hurricane with 155 mph winds — the first Category 4 storm to directly strike the island since 1932. By midmorning, Maria had fully engulfed the 100-mile-long island as winds snapped palm trees, peeled off rooftops, sent debris skidding across beaches and roads. By afternoon, the intense gusts had become less frequent and the lashing rains eased, giving residents their first glimpse of the storm’s wake.

In Guayama, on Puerto Rico’s southern coast, video clips posted on social media showed a street turned into a river of muddy floodwaters. In the community of Juan Matos, located in Cataño, west of San Juan, 80 percent of the structures were destroyed, the mayor of Cataño told El Nuevo Dia. He said half of the municipal employees lost their homes.

“The area is completely flooded. Water got into the houses. The houses have no roof. Most of them are made of wood and zinc, and electric poles fell on them,” the mayor told the publication.

In the capital of San Juan, buildings shook and glass windows shattered from the force of the storm. Residents of some high-rise apartments sought refuge in bathrooms and first-floor lobbies, but even those who sought out safe ground found themselves vulnerable.

Adriana Rosado and her husband decided to stay in the Ciqala Luxury Suites hotel in San Juan’s Miramar neighborhood because it had a generator, and would be able to withstand power outages. It seemed like the safest, most comfortable option for their 2-month-old son to have access to electricity, air conditioning and water.

But Rosado, 21, hardly slept Tuesday night, with the howling winds banging against the building’s windows. At about 4 a.m. Wednesday, Rosado woke to water flowing into the family’s sixth floor hotel room. Shortly after the family left the hotel room, one of its windows was blown out by the storm.

“I just want it to be 10 p.m. so it can all pass, and I can call my family,” said Rosado, sitting on the hallway carpet on the first floor with her baby, Jorge Nicolas, sleeping on a pillow and blanket beside her. Rosado’s neighborhood in Guaynabo, west of San Juan, experienced major flooding Wednesday. She had not heard from her mother since 4 a.m., unable to get cellphone service.

Speaking on NBC’s “Today” show Wednesday morning, Puerto Rico’s governor, Ricardo Rosselló, said conditions were “deteriorating rapidly.”

Buildings that meet the island’s newer construction codes, established around 2011, should be able to weather the winds, Rosselló said. But wooden homes in flood-prone areas “have no chance,” he predicted.

“Resist, Puerto Rico,” Rosselló tweeted. “God is with us; we are stronger than any hurricane. Together we will lift up.”

Already, Maria has roared over islands to the east with winds of more than 160 mph and downpours that triggered flooding and landslides. In the French island of Guadeloupe, officials said at least two deaths were blamed on Maria, and at least two people were missing after a ship went down near the tiny French island of Desirade.

Maria’s fury was clear from its first brush with land. In a breathless series of Facebook posts late Monday, the prime minister of the island nation of Dominica, Roosevelt Skerrit, described furious winds that tore off the roof of his official residence. “My roof is gone. I am at the complete mercy of the hurricane. House is flooding,” he wrote.

Puerto Rico was spared the full force of the Category 5 monster Irma earlier this month. Yet the storm came close enough to cause widespread power outages and weaken the island’s hurricane defenses.

“This is going to be an extremely violent phenomenon,” Rosselló told the Associated Press as Maria approached. “We have not experienced an event of this magnitude in our modern history.”

Before dawn, Maria’s maximum sustained winds of 150 mph were down slightly from late Tuesday. But that meant little for Maria’s ability to threaten anything in its path.

“Maria is an extremely dangerous Category 4 hurricane … and it should maintain this intensity until landfall,” the Hurricane Center said.

The Hurricane Center warned that the rain — possibly exceeding 25 inches in some places — may “prompt numerous evacuations and rescues” and “enter numerous structures within multiple communities,” adding that streets and parking lots may “become rivers of raging water” and warning some structures will become “uninhabitable or washed away.”

Along the coast, the Weather Service described “extensive impacts” from a “life-threatening” storm surge at the coast, reaching 6 to 9 feet above normally dry land.

Puerto Rico is very vulnerable to hurricanes, but it has been lucky as well. The last hurricane to make landfall was Georges in 1998. Just one Category 5 hurricane has hit Puerto Rico in recorded history, back in 1928.

To the north, the remnants of Hurricane Jose brought pounding surf and 65 mph winds to southern New England. Tropical storm warnings were issued for the coast from Rhode Island to Cape Cod.

Jose was also watched closely for its spillover effect on Maria. It could help in keeping Maria away from the U.S. mainland by drawing it to the northeast. However, if Jose weakens too quickly, Maria could drift closer to the U.S. coast by the middle of next week.

Macarena Gil Gandia, a resident of Hato Rey, a business district in San Juan, helped her mother clean out water that had started flooding the kitchen of her second-floor apartment at dawn.

“There are sounds coming from all sides,” Gil Gandia said in a text message. “The building is moving! And we’re only on the second floor, imagine the rest!”

Parts of Hato Rey were underwater. An electric gate for her building in the neighborhood was blown off, Gil Gandia said.

In the lobby of Ciqala Luxury Home Suites in Miramar, a neighborhood in San Juan, Maria Gil de Lamadrid waited with her husband in the lobby as the rain and wind pounded on the hotel’s facade. The door of the hotel’s parking garage flopped violently in the wind. The sounds of the storm were so loud that it was hard for hotel guests to hear each other speak.

Gil de Lamadrid spent the night in the hotel after evacuating her nearby 16th floor waterfront apartment, which has been prone to flooding during previous hurricanes. But even in a luxury hotel room, Gil de Lamadrid could not evade flooding; on Wednesday morning, inches of water began to seep into her hotel room through the balcony doors.

She did not yet know how her apartment building and neighbors were faring the storm. “I’m feeling anxious,” she said. But her husband shrugged, calmly.

“For me, it’s an adventure,” the husband said. “Something to talk about later.”

Irma left many here without power for days. In an unfortunate twist, some residents of Vieques had stocked up on critical supplies in advance of Irma only to donate what they had left to harder-hit areas such as Tortola and St. Thomas. Residents rushed to restock before deliveries to the island stopped and the power flickered off yet again.

President Trump on Sunday declared emergencies in the U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico in advance of Maria. The Federal Emergency Management Agency has embedded workers across the U.S. territories in the Caribbean, including in parts of the U.S. Virgin Islands affected by Irma, to ensure residents have food and water before the storm.

The U.S. military is expected to assist Puerto Ricans after the storm hits, but it is mostly steering clear beforehand to avoid being caught up in it and unable to help, military officials said.

Recovery efforts in Puerto Rico could be hampered by long-standing financial problems that led the territorial government to file for a form of bankruptcy in May.

Hurricane Maria strengthens to Category 5 as it rages toward Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico

Berman and Somashekhar reported from Washington. Daniel Cassady in San Juan; Amy Gordon in Vieques, Puerto Rico; Anthony Faiola in Miami; Rachelle Krygier in Caracas, Venezuela; and Brian Murphy, Jason Samenow, Dan Lamothe and Amy B Wang in Washington contributed to this report.