By KEN RAYMOND

BOLEY — During the late spring and summer, Henrietta Hicks says, this town is so lush and green that it looks like a natural botanical garden.

On this winter day, though, the trees are skeletal. Without its verdant camouflage, the town is exposed: Shops stand empty along a deserted main street, abandoned homes are disintegrating and the patchwork roads are as threadbare as a worn-out pair of favorite jeans. Towering above is the community’s water tower; almost lost amid the rust that covers it is a single word: BOLEY.

Boley, Oklahoma.

Given the town’s history, it hurts to see it like this.

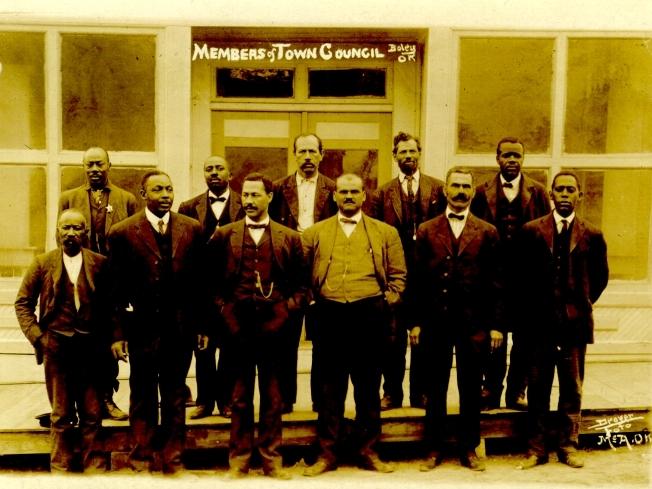

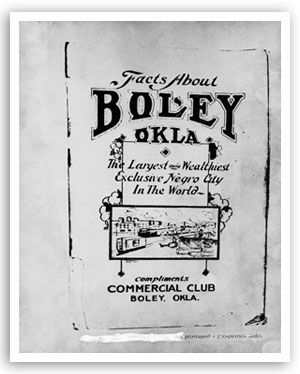

“Boley was once the crown jewel of all the black towns in Oklahoma,” historian Currie Ballard said recently, standing in the rain near a vacant downtown building. “Booker T. Washington came to Boley … twice and deemed it the finest black town in the world — and Booker T. Washington had literally been all around the world. Boley, its significance in commerce, its significance in education, parallels no other black town in the nation.”

PHOTO BY PAUL HELLSTERN, THE OKLAHOMAN

The town, about an hour’s drive east of Oklahoma City, was born from the ashes of the Civil War. The federal government forced American Indian tribes who had backed the confederates to allot land to their freed slaves, and the community was founded along a railroad line on 160 acres within the Creek Nation. It takes its name from a white railway worker, one of three men — white and black — who joined forces to give black Americans this opportunity for self-governance.

The community came together in 1903 and incorporated two years later. The population increased as blacks from other states, fleeing restrictive Jim Crow laws, relocated to the territories. The town, marketed as a place free from racial persecution, grew to include a bank, post office and railway station, as well as churches, businesses and schools. It housed the Prince Hall Masonic lodge and a black hospital. In 1925, it became home to the State Training School for Incorrigible Negro Boys — an institution that would become vital to the town’s sustainability.

“Upon Oklahoma statehood in 1907,” Melissa Stuckey wrote for www.blackpast.org, “the citizens of Boley, like all African Americans in Oklahoma, experienced major setbacks in their civil rights. Although the day to day effects of segregation were muted in Boley, most people in the town were disfranchised in 1910 when the grandfather clause became law. However, Boley was an important location for all blacks in the state as they worked to fight disfranchisement for the next two decades.”

By the late 1920s, the town had reached its peak. Facing tough economic times, in part due to sharecropping and the low price of cotton, people left to find their fortunes elsewhere. The exodus began.

Despite its decline, Boley has managed to limp into the 21st century, surviving long after many of the state’s other 18 to 35 black communities faded.

If town leaders get their way, Boley will thrive again.

PHOTO BY DAVID MCDANIEL, THE OKLAHOMAN

PHOTO BY DAVID MCDANIEL, THE OKLAHOMAN

Mayor Joan Matthews, 66, has a number of revitalization projects in mind. She wants to repair the rusty water tower, which can be seen from two miles away; finish interior construction on a police station, which was struck by a tornado; get the county to repair the roads; and persuade property owners to clean up their land or donate it to the town.

“It’s hard to get people to cooperate, especially absentee owners,” she said. “A lot of the people who own lots here are not from here. They’ve never been here. They don’t even know where the lots they own are, because they bought them in a tax sale. The taxes hadn’t been paid. They paid them, and after a certain time, three or five years, they got the land.”

Trouble is, renovations and improvements take money, and Boley has a limited tax base. Concerned residents and officials recently met with Lt. Gov. Todd Lamb, who assured them he sees the value of their community and wants it to return to glory. But, he said, the state has no money available to help.

Over the years, the school for incorrigible boys transitioned into a Department of Human Services facility before becoming what it is today: the John Lilley Correctional Center, a minimum security prison. At one point, Matthews said, it was the main employer of Boley residents.

As state budgets have tightened, she said, fewer jobs have become available. Those who retire or quit aren’t always replaced.

Still, the importance of the prison to Boley is difficult to overstate. At its heyday, Boley’s population numbered more than 25,000. According to the most recent Census, that figure has dropped to 1,184, including the inmates. The actual number of residents is probably closer to 300, as the total count of female residents is only 160, compared with the prison-weighted male population of 1,024.

With numbers that small, making fixes to the town is a stretch. The water tower alone would cost $175,000 or more, about $583 per resident.

Even so, Hicks, 76, says no one should count Boley out.

“We’re still an all-black town,” she says. “Even though we have two white residents, we’re still all-black. You understand. We’re all black here no matter what color our skin. And we’re going to stay that way for a long time to come.”

WHAT TO SEE

Don’t miss out on a chance to visit Boley, whether you come for the town’s annual barbecue festival and rodeo or for a chance to explore a piece of history. Here are some of the things you shouldn’t miss.

PECAN STREET

The main drag in Boley, Pecan Street is a straight shot through the downtown area. Once the hub of a bustling community, downtown is now largely vacant. Memorable brick buildings, some with boarded-up windows or sagging roofs, stand near occupied structures such as the Boley Community Center. Looking at the buildings, it’s easy to picture how downtown must’ve looked in a busier time, with Model T Fords sharing space with horses on the street and men conducting their business in overalls or fedoras. The buildings bear a weight of history that is almost palpable. To put things in context, seek out unofficial town historian Henrietta Hicks, whose excitement and knowledge make the past come to life.

BOLEY HISTORICAL MUSEUM

Behind the community center, the museum is a repository for various artifacts associated with the town’s history. Small by big-city standards, its charm lies in the quirky juxtaposition of objects. On one wall is a series of framed newspaper articles about comedian Flip Wilson’s visit in 1975, when he became honorary police chief and provided the town with its first police car. On the facing wall hangs a portrait of President Barack Obama. One display is a diorama of an attempted Boley bank robbery in 1932; a woman who visited the museum was inspired to build and donate the diorama, which is accurate in its positioning of the key players. The museum consists of two rooms in a house dating to 1929. It is a source of pride for town residents, who volunteer their time to operate the museum and keep it clean. While it doesn’t provide a detailed overview of the town’s history, the museum does provide a glimpse of some of the significant moments. As such, it is a must-see.

FARMERS AND MERCHANTS BANK

Visitors cannot enter the bank, which is locked up and out of business. They can, however, peer through the windows at ornate marble fixtures and envision how things played out Nov. 23, 1932, when an attempted bank robbery turned deadly. Hicks, again, is the person to seek out for details on the bank robbery; her mother was present that day. As Hicks tells it, three associates of notorious criminal Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd decided to make an unauthorized withdrawal from the bank. George Birdwell and C.C. Patterson entered the bank, while Charles “Pete” Glass, a black man familiar with the town, waited in the car. Inside the bank were two customers, as well as bank President D.J. Turner and a worker, H.C. McCormick, who edged into the vault when he saw the robbers walk in. Birdwell demanded money, and Turner emptied the register. When the last dollar was removed from the drawer, however, it triggered an alarm. Birdwell fatally shot Turner, and McCormick, who’d grabbed a gun from the vault, returned fire, killing Birdwell. “This was November, bird hunting season,” Hicks said. “So when they heard the alarm go off, the townspeople converged on the bank. They took what they had: guns, hammers, screwdrivers, whatever.” Patterson was “riddled with bullets,” Hicks said, but survived. Glass was shot dead as he tried to flee.

WATER TOWER

Boley has a standpipe water tower, of a type common in the late 19th century. Although it looks rough now, preservation techniques could return it to its original condition. The tower, which bears the name of the town, has a funnel top and a bullet shaped body, ringed by a narrow platform. It sits on four legs, supported by scaffolding, and gives the impression of an old-fashioned rocket about to burst into the sky. The tower is one of the oldest in the state.

PHOTO BY DAVID MCDANIEL, THE OKLAHOMAN

BOLEY RODEO AND BBQ FESTIVAL

The town’s signature event each year is the rodeo and barbecue festival, which attracts more than 20,000 visitors. Held each Memorial Day weekend, the two-day celebration includes a parade, concerts, a black rodeo and — as the name implies — hundreds of pounds of barbecued meats.