By: Kate Hairopoulos and Sarah Mervosh

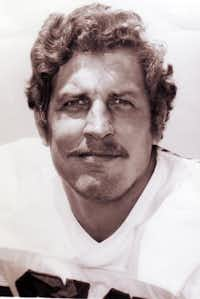

Rickey Dixon always hit hard. During his high school football days in Dallas, his career at the University of Oklahoma and his six seasons in the pros, he used his head to smash into his opponents — not just to tackle them, he says, but to demolish them.

Today, he needs help from his 9-year-old daughter to brush his teeth.

Brain injuries have left him almost paralyzed, trapped inside a body that has shrunk to just 115 pounds. At 51, he can’t work; he can scarcely move; he cannot speak at all. He hears his wife crying in the night, he wrote recently, “but I’m not able to walk over to her to wrap my arms around her to comfort her.”

For his family, Dixon says, he is fighting against the lawyers he once hired to pry compensation for his injuries from the National Football League. Instead, he says, they are trying to take money that should go toward his care and the future of his wife and four children.

Dozens of other ex-NFL players and their families, including the daughter of a retired Dallas Cowboy, have been waging similar battles, according to court records. Hundreds of families could be affected by what a judge decides about legal fees that amount to millions of dollars — fees many of the lawyers say they earned.

This wrangling threatens to bog down the historic settlement that the NFL reached to pay 20,000 or so injured players as much as $1 billion over more than six decades.

Disputes over legal fees are not uncommon in high-dollar cases, especially class actions. But the fights in this case also highlight the struggles of stricken football heroes and their families to cope with the aftereffects of concussions that the NFL and its players once considered just a part of the game.

No one worried about brain injuries when George Andrie started playing for the Cowboys in 1962. A member of the team’s legendary Doomsday Defense, he played alongside “Mr. Cowboy” Bob Lilly for most of his 11-year career and ranks among the franchise’s top five all-time in sacks. When Andrie scooped up a fumble and ran it for a touchdown in the famous “Ice Bowl,” the glacial 1967 NFL championship game against the Green Bay Packers, he became part of franchise lore.

Yet he never made more than $36,000 a year from the Cowboys, his family says, and sold real estate in the offseason. After his playing days, he started a second career selling customized caps, mugs and other items companies use to promote their businesses. He and his wife — and their seven kids — settled near Waco.

But over the years, Andrie started having unexpected problems. He became depressed. His temper shortened. He began forgetting where he was driving or why he got up from his chair. He’d jot down a note to help himself remember, then forget where he’d slipped the piece of paper.

Scientists now know that playing football is linked to brain damage. In one of the largest studies of retired NFL players, released last year, more than 40 percent had signs of brain injury. Autopsies of some former players have found significant cerebral damage.

Players started suing the NFL in 2011. They alleged that the league had been aware of the risk associated with repetitive hits to the head, but failed to warn and protect them. In these cases, the players did not have to pay anything up front, but the lawyers would get a big cut if the league ever paid up.

Eventually, the thousands of individual lawsuits were consolidated into a class-action in federal court in Philadelphia. In 2015, the court approved a settlement in which the NFL agreed to a $1 billion payout; each player’s potential award depends on his diagnosis and age. After many court challenges, the deal became official in January.

The court appointed a group of lawyers to work on behalf of all players who had symptoms of brain trauma or might develop it in the future. That legal team is to split $112.5 million in fees paid by the NFL.

But some members of the team also want payments from their individual clients. They say they deserve the money for all the work they have done and time they have spent on individual cases.

“Our firm has invested thousands of hours and hundreds of thousands of dollars in this litigation, but has not received a single penny in compensation,” says one of the lawyers, Steven C. Marks.

As the legal battle was grinding on, Andrie went to see a doctor. He just wanted to find out “what the hell is wrong with me,” he says.

He got a diagnosis of dementia in 2014. He also has mini-seizures which cause short-term memory loss, and aphasia, a type of brain damage that inhibits his ability to understand and express speech.

He now looks at pictures of his days as a defensive end and notices the paint that chipped off his helmet from hits dished out and taken. It was common back then to keeping playing, he says, even when he had his “clock rung.”

Andrie, who turns 77 this month, remains 6-foot-5 and broad shouldered. But he can’t stand up straight anymore, and he hobbles to and from a leather recliner in his man cave. He shared his story for the first time — he’s proud to be from a generation that doesn’t complain — in the hopes that it may help other former players.

His daughter, Mary Brooks, worried about how much it will cost to care for her father and 76-year-old mother, Mary Lou, who uses a wheelchair.

Brooks set about making sure her dad would receive his due from the settlement: as much as $158,000 — enough to pay for two years of in-home care for her parents and have a little leftover, she says.

She says she was surprised to learn recently that back in 2012 her parents had signed up with lawyers who represent 1,400 players. Her father didn’t remember it and her mother didn’t understand what they were signing, they say.

Brooks says she was determined to keep them from taking any of her father’s award. One of the lawyers involved said he would not pursue fees; another declined to comment on her case.

A hair stylist in Austin, Brooks says she found a support network through a private Facebook page of wives of former and current NFL players.

She learned the stories of former players like Mike Davis, who spent nine years in the NFL and now suffers from hearing loss. And of retired Los Angeles Raider Steve Smith, who lives in Richardson and is so sick that he has been on a ventilator a decade

Dixon used to tell kids he was a long shot to make it out of Dallas, where he went to Wilmer-Hutchins High. His father died in a construction accident when he was in diapers. His mother raised five children by working long hours as a maid.

OU coach Barry Switzer took a chance on Dixon, who became an All-America defensive back. His teammates once voted him the Sooners’ hardest hitter, even though he was one of the smaller players on the field.

He went on to be selected No. 5 overall in the 1988 NFL draft. He played for the Cincinnati Bengals and Los Angeles Raiders, appearing in Super Bowl XXIII.

He went on to become a motivational speaker for at-risk youth. He taught physical education at Red Oak, the town south of Dallas where he lives, and other public schools here.

Then, in 2011, he realized he could no longer feel the rub of money when he counted it. He began losing weight. By 2013, he fell while jogging on a treadmill, so his wife sent him to the doctor.

Dixon’s diagnosis: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, or ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease after the famous baseball player. It progressively weakens and paralyzes muscles, so that it becomes difficult for patients to to talk, swallow, or even breathe. Some researchers have linked the disease to concussions.

These days, Dixon withers in his striped Adidas sweatsuits and matching sneakers. Stripped of his voice, he uses his big, dark eyes and a contagious grin to communicate.

When the weather is nice, he and his 9-year-old daughter take excursions to the stop sign down the street: he in his motorized wheelchair, she on her bubblegum-pink hoverboard. The Mercedes convertible he bought to celebrate being drafted by the Bengals gathers dust in the garage.

For Dixon, the $4.5 million payout will not translate into a life of luxury. He has his family to think about, including his 20-year-old disabled son, who will need care for the rest of his life.

Dixon’s wife, Lorraine, who he met during their college days at OU, says the family would use the money from the NFL to replenish their retirement and college funds, which she has had to use to pay for Dixon’s care. She would also like to remodel their house to make it handicapped-accessible for her husband.

“For us, this is not buying a big house and a new car,” says Lorraine, 48. “It’s just survival.”

Back in 2012, as Rickey was getting sicker, the Dixons hired a lawyer, Charles Zimmerman, to take on the NFL. In a recent interview, he said he took on the case at no cost and went up against the league “well before reporters, movie producers or anybody else was looking at this problem.”

He says he did a lot of work, including helping the Dixons to get a loan to tide them over as the case progressed. “Then when it came to fruition, and there was actually a dollar amount put on the case,” Zimmerman says, Dixon fired him in 2015.

He is asking the court to give him 20 percent of Dixon’s award, or $900,000, which is less than he originally agreed to and, he says, is “more than justifiable.”

The Dixons contend in a court filing that he has done too little work to justify a cut of their reward. They included an invoice from his law firm that totals just over $2,300 (though it includes only expenses like copying and postage, not his hourly fees).

“I don’t mind paying lawyers,” says Lorraine, who is herself a lawyer for the Environmental Protection Agency in Dallas. “I respect the craft, their expertise. But don’t try to milk us for things you didn’t do.”

As fans might expect, Dixon is fighting hard — this time in court.

Over the course of two weeks, morning to night, he wrote a letter to the judge using a special computer that tracks his eye movements to pick out letters. When his eyes grew sore, his wife soothed them with a warm wash cloth. When that wasn’t enough, he switched to texting, painstakingly tapping a cell phone with his knuckles.

Please, he argued, don’t let the lawyers take a chunk of his settlement.

“For me at least, there are no second chances,” he wrote. “My body is too badly damaged to do much of anything. My last efforts will be on behalf of my family.”

The judge, Anita Brody, is expected to schedule a hearing soon on the fee disputes. Depending on the outcome, the money could finally start flowing this summer.