WASHINGTON — The black and brown faces stare out from the Metropolitan Police Department’s official Twitter feed, each girl under a red banner with block letters declaring “Critical Missing.” Their names speak of unseen corners of the nation’s capital, a world far removed from lobbyists’ power lunches and legislative deal making.

Osharna Pittman, 13, last seen wearing a burgundy T-shirt, white jeans and a pair of silver Puma tennis shoes. Seyauna Parker, 14, last seen on March 23, her eyes looking downcast and sad. Keyara Edwards, 15, in braids and smiling. Anjel Burl, 16, her red hair tucked into a yellow knit cap. Each post contains a simple query: “Seen her?”

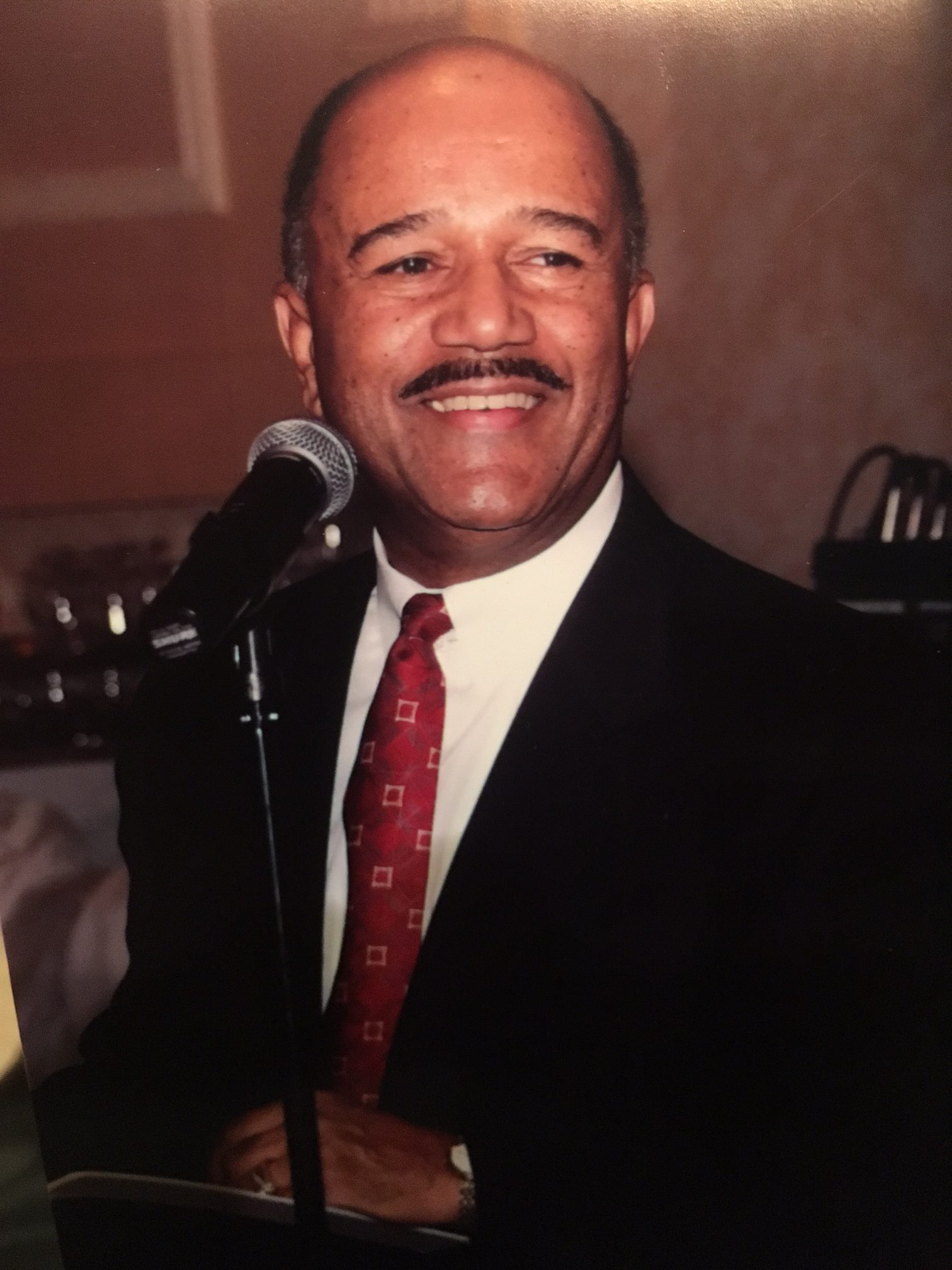

In those faces, Cmdr. Chanel Dickerson saw a reflection of her own childhood here, and of an 11-year-old neighbor whose mother had sold her into prostitution in exchange for drugs. So when Commander Dickerson was promoted to lead the department’s Youth and Family Services Division in December, she decided to “get the word out,” she said.

It worked. The hashtag #MissingDCGirls started trending on Twitter, fueled by social media posts from celebrities, including the rapper Ludacris and the actress Viola Davis. A member of the city council declared an “epidemic” of missing girls, and hundreds of angry residents turned out for a town hall-style meeting, demanding to know what was going on.

At the Capitol, members of the Congressional Black Caucus asked Attorney General Jeff Sessions and the Federal Bureau of Investigation to investigate. On Wednesday night, dozens of community activists and parents — including a mother who said she had struggled to get help from the police when her 12-year-old child was missing for a week — gathered outside the African American Civil War Memorial for a Protect Black Kids candlelight vigil.

In truth, there is no surge in disappearances; reports of missing children here have actually declined over the past year. But in this city of haves and have-nots, the uproar has exposed a part of the capital the rest of America rarely sees, and it points to a deeper and more nuanced problem: at-risk youths, disproportionately black and Latino, whose lives and struggles — sometimes involving sex trafficking — are often ignored by public officials and the news media.

“There is no epidemic in the nation’s capital of people being snatched,” Mayor Muriel E. Bowser, a Democrat, said in an interview after announcing steps to improve social services and police response, prompted by the public outcry. “But that doesn’t mean there aren’t children that need our help.”

The police say 2,242 children were reported missing here last year, down from 2,433 in 2015. Commander Dickerson says that 99 percent of the children are found, and that many are running away from difficult situations at home. As of Saturday, there were 18 open cases of missing young people, all of them minorities. Half were girls.

Nationally, about 35 percent of missing children are black, and roughly 20 percent are Latino, said Robert Lowery, vice president for the missing children division of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. In that regard, he said, Washington is not “unique or out of the ordinary.”

But the vigil on Wednesday evening, in a small plaza near a Metro station bustling with commuters, offered a peek into this wealthy city’s racial divide. African-Americans, who used to be a majority in Washington, now make up 49 percent of the population. Aisha Jackson, 60, a teacher, held up a handmade sign that said “Find Our Children!” and lamented that gentrification was changing the city, driving the problems of the poor deeper into the background.

“It pains me that no one cares,” she said.

Elsewhere in the country, the sudden flurry of social media posts has prompted a painful conversation about how law enforcement and the news media treat some of the most vulnerable Americans: black and Latina girls.

“The bottom line is there is an anti-blackness, an anti-brownness that exists in every conversation you could ever have about social issues in our society,” said Tamika D. Mallory, a civil rights activist in New York who helped organize the Women’s March on Washington in January. “And if you allow white media to tell your story, it won’t be told.”

That frustration is a major reason the #MissingDCGirls hashtag exploded. Danielle Moodie-Mills, whose Twitter profile describes her as an “equality advocate,” shared some images of missing girls in a single post that asked, “Can someone explain to me how 14 black girls go missing in 24 hours in DC and it’s not a goddamn news story?!?”

Her figures were off, but the post was one of several that went viral, prompting outrage among people like Ashley Love, a New Orleans writer and mother of three.

“If it would have been a white girl, it’s usually blown up,” said Ms. Love, who joined in the Twitter tirade. “You would have seen it on CNN; you would have seen the Amber Alerts.”

Here in Washington, Amber Alerts — the national emergency response system used to spread news that a child is missing — have been a big topic of conversation. The system is put into use only when a child is abducted.

“The Amber Alert criteria needs to change,” said Sharece Crawford, a community leader who has been consulting with the police and the mayor. “If the criteria cannot change on a national level, a new system needs to be created for the D.C. government. There should be no reason why you have to go down a checklist if your child is missing.”

She and other advocates accuse the mayor and the police of a “blame the victim” mentality, and complain that they are trying to mollify the public by dismissing the problem as simply an issue of “runaways.” Phylicia Henry, director of Courtney’s House, a nonprofit here that counsels sex-trafficking survivors ages 12 to 21, said a large percentage of the missing list were referred to her group by the police.

“To say, ‘Oh, they’re just running away,’ is troubling,” she said. “The biggest indicator of a young person being sex-trafficked is this revolving door of going home and leaving home.”

Keyonna Atkinson, 18, and Christian Cooper, 20, both have spent time on the Police Department’s “critical missing” list. Today, each has a tiny apartment in an independent-living center on Capitol Hill operated by Sasha Bruce Youthwork, a nonprofit that offers housing and counseling to homeless and at-risk youths.

Join a deep and provocative exploration of race with a diverse group of New York Times journalists.

Ms. Cooper ran away for a month to her boyfriend’s house when she was 15, she said, and was thrown out of her mother’s house when she became pregnant at 17. She wound up living with an older man who gave her money and lavish gifts, she said, but was physically abusive.

Ms. Atkinson, describing herself as “rebellious,” clashed repeatedly with her mother and elderly aunt, seeking refuge at a local recreation center. Her family reported her missing almost nightly, she said, triggering a response by the police, which evolved into kind of a routine.

Ms. Atkinson had depression, she said, but lacked mental health care. She eventually left home and wound up in a homeless shelter, terrified, before landing a coveted spot at the Sasha Bruce center six months ago. She is now going to school for her equivalency diploma.

“When I turned 18, I cried all day, wondering, did I have the skills that it takes to be an adult?” she said.

Debby Shore, executive director of Sasha Bruce Youthwork, said the city needed to intervene earlier, before kids disappeared.

“Winding up on that list is a sign that there’s family conflict,” she said. “Typically these are young people that have chosen out, that blow out of the house because there’s been some kind of struggle.”

In response to the public outcry, Mayor Bowser has said she will assign more police officers to find missing children, and establish a task force to determine what social services families might need. She said she was hoping to make her city a national model, adding that until Commander Dickerson started posting the reports on Twitter, “I didn’t recognize the substantial number that we get on a daily basis.”