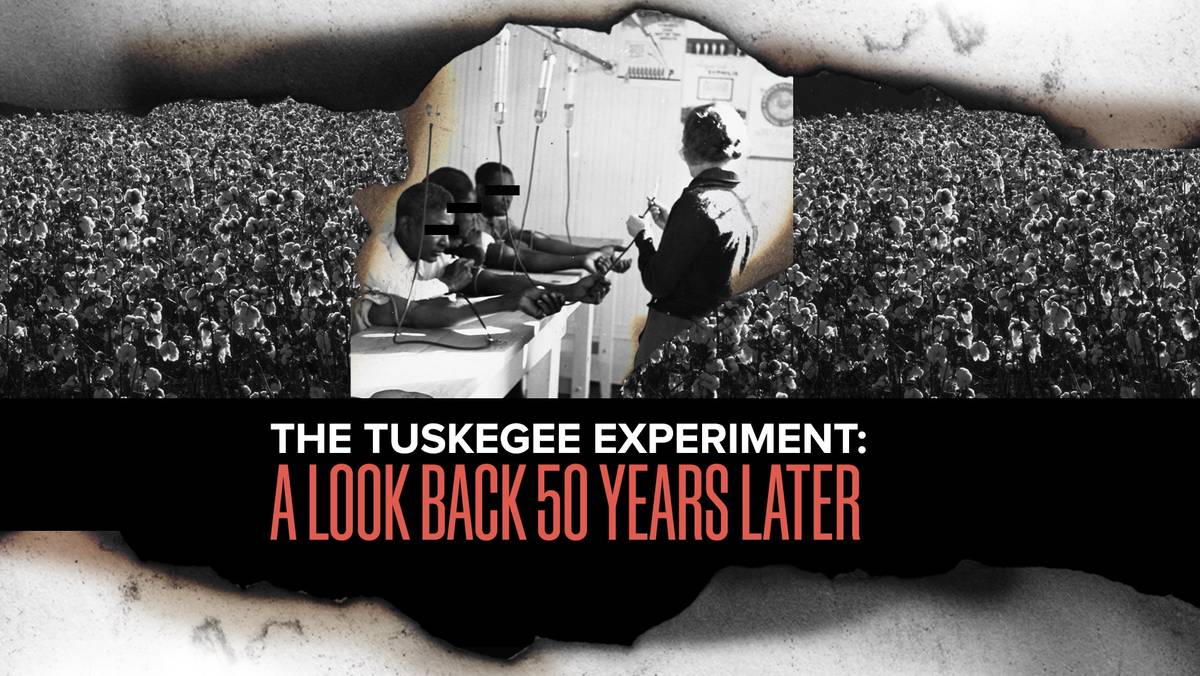

From 1932 to 1972, U.S. government scientists experimented with the lives of poor Black men without their knowledge and got away with it. Here’s a historical explanation into exactly what happened.

Macon County, Ala., bears a history that seems to run parallel with that of the United States itself. On the one hand it is where in 1881, Booker T. Washington chose to establish what is now the Tuskegee University, educating thousands of future Black leaders and preparing them for economic independence.

On the other hand, those same roads in Macon County in the early 1930s bore the lengthy and terrible embossed signature of racism. What happened there from 1932 to 1972, historians look at as one of the most insidious acts of brutal scientific exploitation in U.S. history. In the four decades that it took place, much of the American medical community that knew about it – including public health officials – simply looked the other way.

Why? It started out as an attempt to treat a rural Black population afflicted with a syphilis outbreak but turned into a nefarious opportunity to exploit Black men for what government medical agents felt was sound science.

The physicians involved thought of it as beneficial to society, but what was known as the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male only lives in historic infamy today.

How It Began

The roots of the Tuskegee Experiment were in many ways just as nefarious as the study itself. According to a paper written in 1978 by Harvard University historian Allan M. Brandt, between 1890 and 1910, doctors studying sexually transmitted infections (STI) in Oslo, Norway withheld treatment from almost 2,000 patients infected with syphilis, a bacterial infection known to be spread through sexual contact. If left untreated, those infected could suffer blindness, mental health problems, heart, brain and nervous system damage, and in some extreme cases, death.

At the time, most doctors treated syphilis with Salvarsan, a drug which treats the bacterium that causes syphilis. However, the drug was found to be toxic in humans and ultimately ineffective to those who had advanced syphilis.

Doctors had already observed a syphilis outbreak in rural Alabama, and public health advocates had called for it to be addressed. In 1929, the Chicago-based Julius Rosenwald Fund, a philanthropic entity that donated money to various charitable causes, gave a grant to the United States Public Health Service (USPHS), a predecessor of several current U.S. government health agencies, to study occurrence of syphilis in Black people in the rural south. Researchers found an outbreak of the disease in Macon County – which had the highest rate of the six surveyed counties and determined it was the perfect test case for mass treatment.

The same year, the nation was suffering through the Great Depression and the funding for a treatment project collapsed. Dr. Taliaferro Clark, who authored the Rosenwald study report, was Chief of the USPHS Venereal Disease Division and felt that the Macon County cases allowed for an opportunity to observe the progression of the disease. Observers of the Oslo study believed syphilis affected Black people differently than it did White people. Syphilis can remain latent in many patients and a large number of Black men there had lived with the disease despite showing no symptoms. To Clark, this was a chance to study the natural course of the disease. He communicated his theory to then-U.S. Surgeon General Hugh S. Cumming, who thought the research could have a result on treatment.

Many in the venereal medicine field believed experimenting on Black people presented a unique opportunity given their beliefs that these men were typically poor, uneducated, promiscuous, and unlikely to seek medical treatment, and as much so was indicated in Brandt’s paper.

For the entire article got to: www.bet.com