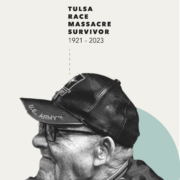

James Osby Goodwin, 79, is a lifelong Tulsan, an accomplished attorney and the owner of Tulsa’s only black-owned newspaper, The Oklahoma Eagle. He is an advocate for the city’s reconstruction of the Greenwood District, for its history both before and after the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. It’s a part of his family’s story, and he is devoted to restoring and revitalizing Greenwood while carving out the massacre’s proper place among not only Tulsa’s, but also America’s, history.

Goodwin is one of eight siblings who grew up next door to Tulsa’s St. Monica Catholic Church, before his father purchased a 150-acre farm in the community of Alsuma at East 51st Street and South Mingo Road. Nearby railroad tracks separated whites and blacks. At 9 years old, Goodwin became an amputee when he lost his right arm in a horseback riding accident that involved a train on the Katy Railroad. Despite his disability, Goodwin has never allowed it to stand in the way of his academic and professional success.

Where did you go to school/university? Why?

I left Tulsa in 1955 — the year the city was going to desegregate. I went to Springfield, Illinois, for my junior and senior year of high school. I went to live with my grandmother and my aunt, so I could attend Cathedral Boys High School, an all-boys Catholic school. The reason for that transfer was that I was very active in academics, theater and student government, but I didn’t feel I was as informed as I ought to be. So, I asked my folks if I could go to school elsewhere.

After I finished Cathedral Boys High School, I attended Notre Dame. As a sophomore I got into a program that was just beginning at many universities, where you studied the great books of the Western world. It had a special curriculum with limited admission of students. My greatest crowning moment at the end of my college career was when I wrote a paper about “Ulysses” by James Joyce. (He scored the highest on the assignment.) I graduated from Notre Dame in 1961 and went straight to law school at the University of Tulsa.

You mentioned how your early days were influenced by the Catholic faith as a parishioner at St. Monica’s. Is Catholicism still important to you today?

I’m still a practicing Catholic. At Cathedral Boys High School, I reconnected with my Catholicism. Being close to the nuns and convent as a child, we were baptized when we were young. My mother would say, “I don’t care (to) which church you belong just as long as you’re in church.” Prior to my 10th grade year, I grew up under the influence of Baptists and Methodists. In the Baptist church as a youngster, I could be inspired by the sermon with a burst of hope and truth, but 30 minutes later I was hungry again. I never knew why I felt the way I felt. When I got to Cathedral Boys High School, I was introduced to the logic of our faith and it gave me a reason for believing, so that I could better understand the nature of my feelings as I read the Bible.

What was one of your most defining moments in life?

Probably the amputation of my arm. It was a time of reflection. I had a horrible temper as a kid, and that sort of tempered it. It made me stronger and redirected my energy.

What keeps you feeling young and why?

My practice of law — I’ve been at it for 54 years. It’s still an inspiring endeavor to which I look forward every day. There’s never a dull moment.

How would your friends describe you?

I can’t answer that, really. My mother always referred to me as “gentleman Jim.”

What would people be surprised to know about you?

I’ve been involved in a men’s group for over 25 years with some very interesting people. We’ve met every Thursday. We meet to talk about our lives in context of, “What would Christ do?” It has had both ex-gang members and the very wealthy in it.

What is your hope for the future of Tulsa?

We are at a very propitious and redemptive moment in the history of Tulsa. We are about to come upon our centennial of the massacre. I wrote an article in our paper called “How to Make Greenwood Great Again.” There’s ambivalence about our history that even in 100 years Tulsa has not reckoned with the root causes of the 1921 massacre. Why is it that Tulsa has one street with two names, divided by a street that, before 1921, separated white Tulsa from Tulsa’s black belt? Why is it that on Greenwood there are two state universities, side by side, one historically white and the other historically black, managed by the same board of regents, when only one university should suffice? Finally, other evidence of that ambivalence manifests itself in perennial debates on whether to refer to the 1921 carnage as a “riot” or a “massacre” or change the name of the business district, adjacent to the Greenwood District, named after a white supremacist, who participated in the bloodletting.

I believe the centennial is a moment that we can, as a city — a body politic, turn a tragedy into triumph. It’s not about vilification, but rectification. Emphasis should be devoted to the reconstruction of Greenwood, not its gentrification nor reparations. The history of Greenwood should be told in bricks and mortar on the outside, and its history on the inside.

I’d like to see in the immediate future the creation of a destination for the world to come visit and recreate Greenwood through high-tech virtual reality. There could be an interactive series of places where people could come and witness the events of before, during and after the massacre. Hundreds of thousands of people can come here to Tulsa and view that reality. There’s a shame that people feel even today — a certain kind of guilt that we can resolve by embracing the good and looking at the bad. This should be a communitywide effort to tell a story, make it a tourist destination, which would then provide business opportunities, jobs and income within the neighborhood and blend in with other adjacent cultural sites. If you could walk into an interactive museum and hear the sounds of the bombing and the stories of people, it could be a phenomenal experience. It would uplift Tulsa. We need to call it what it is and preserve that history. It’s a part of Tulsa’s story and a part of Oklahoma’s story — a story not only about a people who suffered from racism, but a story of their resolve.

What kind of legacy do you hope to leave for Greenwood?

All my life, I’ve tried to bring some leveling force of influence in this community because when I was growing up, many black folks were consigned to being maids, butlers and chauffeurs. When urban renewal came through here, I asked my father to negotiate for me an option to purchase all of the buildings left on Greenwood. He bought it as an option from the Tulsa Development Authority, and I held onto it for 15 years. When Jimmy Carter became president, I assigned my option to the Greenwood Chamber to buy. It was then able to get a redevelopment grant. I did that because I understood, as a kid, the historic significance. I saw the hustle and bustle of commerce after ’21. The reconstruction of Greenwood will be the city of Tulsa’s affirmation that black Tulsans are an integral part of America, and part of the American Dream.

What about your role with The Oklahoma Eagle — what keeps you so involved?

I would like as a legacy, if I could, to have a media institute that specializes in evaluating the impact that black, Hispanic and Native American journalism has had alongside jazz, gospel and blues, on American society. We will always need the press, investigative reporting and a vehicle to fight for the underdog. That’s why I think the black press is so important today. There are few left to champion the cause. That’s what keeps me running The Oklahoma Eagle — a necessity to often times be that voice crying in the wilderness.

What was a “worst time,” and how did you pull through it?

We’ve filed bankruptcy twice at this newspaper. Those were the worst times. It was a matter of faith, really, a deep faith. Benefactors at the time — including the former head of Williams Co. Keith Bailey; the two leaders of ONEOK, Larry Brummett and his successor David Kyle; and another unsung hero, Stuart Price (in addition to Goodwin’s wife, children, brothers, sisters and other members of the community) — they were wonderful people who saw our efforts and generously supported us.

What concerns you today?

The prevalence of racism and bigotry engrained in our society. Racism and racial superiority is visibly creeping itself back into society today, the kind of racism which expressed itself in the complete annihilation of 36 blocks of Greenwood at a time when it was a microcosm of New York City.

How do you measure success?

It’s certainly not the size of your bank account, house or car. It’s the quality of how you deal with people. There were two guiding principles etched in my mind as a kid. My mother would say, “For what does it profit a man if he gains the whole world and loses his soul?” My father would often remind me, “A man who does not take care of his family is worse than an infidel.” It’s amazing how you don’t necessarily know how they impact you but you can, in reflection, realize those principles.

What is a favorite Tulsa memory, or what place in Tulsa do you miss the most?

The prosperity that was once here in Greenwood that I experienced as a child is what I miss the most — the vitality of the area.

Describe a perfect weekend in Tulsa or elsewhere.

I like going to dinner with friends and spending time with family over the holidays. I love the arts and music that Tulsa has to offer. It’s a precious place. I love horseback riding. I had a horse since I was 7 years old until the 1970s. After my children grew up and graduated from college, I bought another Palomino, Bailey.