Bynum: City to spend ‘$1 million to continue the search for the graves of victims.

By GARY LEE AND JOHN NEAL

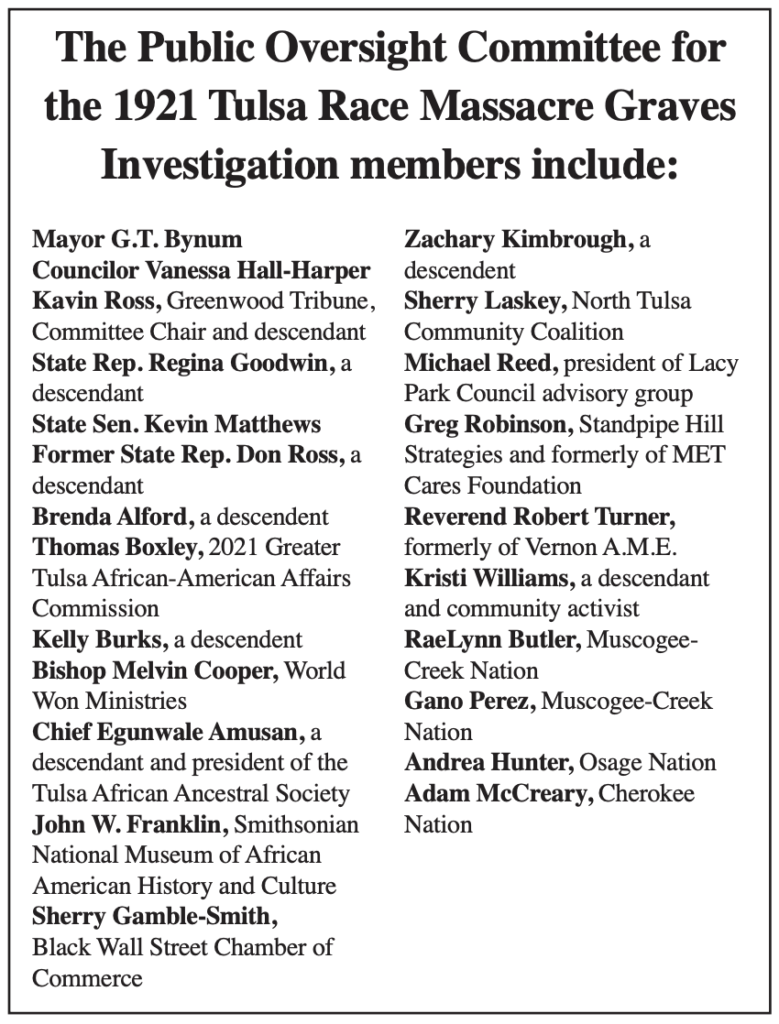

Several members of the Public Oversight Committee for the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Graves Investigation monitoring the investigation of the mass graves of victims of the 1921 Race Massacre have raised new questions and doubts about the commitment of Mayor G.T. Bynum – and other Tulsa leaders – to discover where the bodies of the victims are and who is responsible for their deaths.

The critique launched by members of the Oversight Committee– all prominent African American Tulsans – comes a year after the start of excavations for the mass graves. It also follows a report about the graves that the University of Oklahoma’s Oklahoma Archaeological Survey, which is conducting the probe, issued on March 1. The report included several suggestions to move the investigation forward, including a recommendation to broaden the excavation at Oaklawn Cemetery, the current focal point of the probe. The criticisms also follow a public pledge by Bynum to commit further funds to the investigation.

Bynum has doubled down on his public stance supporting the grave’s probe.

“We have been working to determine the necessary budget to go toward the recommended next steps of the investigation,” he said in a statement to the Oklahoma Eagle. “The proposed budget (for 2023) will include $1 million to continue the search for the graves of victims from the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, which includes further excavation work and DNA analysis following the recommendation of technical experts submitted to the city earlier this year. We continue to await DNA analysis results and are currently in the planning phases for the next excavation at Oaklawn Cemetery.”

Bynum has also confirmed his position that the mass grave probe is a crime scene investigation rather than simply an archeological dig.

‘Superficial, cynical and inadequate’

But members of the Oversight Committee questioned the mayor’s sincerity. The Oversight Committee is composed of 24 members, many of whom are residents of the Historic Greenwood District. Some are descendants of victims of the Race Massacre.

Chief Egunwale Amusan, an Oversight Committee member and one of its the most vocal critics, dismissed Bynum’s promises and the official status reports – as “superficial, cynical, and inadequate.”

In an interview with the Oklahoma Eagle, Amusan, who is a descendant, said, “At this stage, what people want to know is whether a crime took place and what the city will do about it.”

He added that the report and Bynum’s statements are likely to add to the confusion rather than provide answers or clear direction.

Other members of the Oversight Committee, including North Tulsa massacre descendants and community advocate Kristi Williams, State Rep. Regina Goodwin and journalist and documentarian Kavin Ross also expressed some concerns about the Tulsa leadership’s approach to the mass graves investigation. Ross, an Eagle contributor who also runs the Greenwood Tribune social media channel, is the Oversight Committee’s chair.

Ross told the Eagle that he is concerned that the city is not taking all the precautions it should take to care of the gravesites at the Rolling Hills Memorial Gardens – formerly the Booker T. Washington Cemetery – and Oaklawn.

“We should not forget that these are sacred grounds,” he said, “and they should be treated as such.”

Where is the $1 million going?

Williams said she continues to question the city’s strategy.

“The city’s approach to the graves is further proof that we can’t trust a process in which the massacre perpetrators are supposed to be investigating themselves,” she said.

Since the city of Tulsa was complicit in the massacre, she explained, they can’t conduct an independent probe into what happened. Besides her role on the Oversight Committee, Williams also chairs the Greater Tulsa African American Affairs Commission.

Goodwin, who is also a descendant, agrees with Williams and is concerned about the city’s actions.

“The assessment of where we are gives the illusion of some effort,” she said in an interview with the Eagle. “But it’s been many years, and we still don’t have any answers to the key questions. Nor do I see any serious attempt to answer them.”

Goodwin also questioned the $1 million Bynum has committed to the mass graves investigation. “It sounds impressive, “she said. “But I want to know where that money is going.”

Status of investigation

The March 1 report, titled “Archaeological And Forensic Research In Support Of The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Graves Investigation,” essentially summed up the history and status of the probe. It was compiled by Kary L. Stackelbeck, Oklahoma’s State Archaeologist, and Phoebe R. Stubblefield, the interim director of the C.A. Pound Human Identification Laboratory at the University of Florida.

“The corpses of African American Massacre victims, which numbered in the scores if not hundreds, weren’t regarded as anyone’s father, mother, sister, brother, son or daughter,” the introduction says. “For years, rumors persisted among reports of bodies dumped in the river, incinerated, or hauled away on the flatbed rail cars. But many, if not most, we can with fair confidence assume, were dropped into freshly dug graves or in a mule or machine-drawn trenches. They had no regard for their remains or how they were buried while their families were held under armed guard.”

The report also reminded readers that the initial search for the mass graves, conducted in 2001, focused on three possible locations: Oaklawn Cemetery, Newblock Park and Rolling Hills Memorial Gardens. The current investigation, opened in 2018 by the city of Tulsa, states those previous researchers “compiled a substantial amount of evidence” of a historical and scientific nature, aided by interviews of the descendants of victims. In subsequent years, an area adjacent to Newblock Park, The Canes, was added as a potential site bringing the total search locations to four.

When OU’s Oklahoma Archeology Survey team took up the current effort, they had to take cautious steps in their exploratory process. Their work was made more complicated by the passage of time, shifting soil conditions and sketchy historical records. In the March report to the city, the authors cite the callous indifference whites treated the burial of their Black victims.

This is partly because even in 1921, white authorities wanted not just to understate casualties, but the violence itself. “They had already begun to bury the massacre itself,” the report notes.

Efforts were made over the years to keep these burials secret.

University of Michigan historian Scott Ellsworth – a co-author of the March report and who wrote the first comprehensive history of the massacre in 1982 – had previously written that in the 1920s the city of Tulsa had rejected outside efforts for aid and assistance for victims, saying instead they would provide service and reparations in a blatant attempt to cover up the massacre.

Nevertheless, the new archeological team was armed with information from the previous investigation and completed geophysical surveys of all four locations in 2019 and 2020. The purpose of the surveys “was to identify anomalies that might represent targets for ground-truthing through test excavations.”

As a result of these tests, one area of the Oaklawn Cemetery suggested the presence of a mass grave.

In March 2021, the 24-member Oversight Committee approved the excavation and forensic analysis of potentially exhumed remains. Many of the Oversight Committee members are residents of the Historic Greenwood District, some descendants of victims of the massacre.

Before excavation, in the summer of 2021, special precautions were necessary. Stackelbeck was a principal leader of the excavation team.

In a video explaining the process, she said, “We were also very concerned about the fragile state of the remains and their condition. We did not want to take any steps too prematurely that would potentially expose the remains and potentially limit the subsequent forensic analysis.”

Evidence of Physical Trauma

The area excavated yielded 34 burials, 19 of which were exhumed, and 14 of the 19 were sampled for DNA to be sent to a laboratory for further analysis. However, 14 fancier coffins presumably containing women and children were left in the ground and not exhumed. One adult male had evidence of physical trauma, in this case, gunshot wounds.

The 14 sets of adult DNAs extracted are to be sent to a forensics lab for testing, including their viability for matching. The archeological team remains unsure whether these remains are victims of the Race Massacre. DNA testing may help.

The Oklahoma Archeological Survey team made their final recommendations that the city and the DNA consultant develop a plan to inform and encourage community members to participate in the DNA analysis to match the adult remains they are testing.

Other recommendations included expanding the excavation to find “the possibility of one or more traditional mass graves (existing) elsewhere in Oaklawn Cemetery.”

They also recommend additional geoarchaeological investigations in Newblock Park and The Canes.

However, in the Council meeting on March 2, 2022, the councilors were told that the cost for the additional excavation and geoarchaeological investigations was unknown and would only become more apparent in responses to a “Request for Proposals” yet to be submitted.

Several contentious disputes have surfaced between the Oversight Committee, the archeological team and the city during the current investigation. They immediately followed the excavation activity in June and July 2021 and continued through numerous interim meetings. Including presenting the final report on March 1, to the Oversight Committee and the Council.

Is Oaklawn a homicide scene?

One constant issue is whether the undertaking is a homicide investigation, an archeological dig, or an effort to find victims murdered in the Massacre? The Oversight Committee was troubled by the shift away from a homicide investigation.

Although Bynum has publicly concurred that the probe is an investigation of a crime, members of the Oversight Committee pointed out that the search is not being investigated as a crime.

“There is nothing the city is doing to show that they really view this as a murder investigation,” Amusan said. “We have to hold them accountable.”

Another question is over why only the graves of males were exhumed?

Women and children were undoubtedly victims of the Massacre.

The investigation team gave the Oversight Committee a variety of answers. Some of them hinged around the fact that all the “Original 18” victims recorded burials at Oaklawn were male. The archeological team confusingly stated that the “target” was Black males in plain burial boxes whose remains had evidence of trauma.

The more ornate coffins, like those with handles, were presumed not to be massacre victims and fit a pattern more likely to be women and children. Thus 14 states of remains, some with bodily remains partially exposed in deteriorating coffins, were not exhumed, and later covered back up with dirt.

Williams told the Eagle that she disagrees with the focus on males.

“It stands to reason that they should be included,” she said. “We know that women and children were massacred.”

The Oversight Committee also objected that the 19 bodies were reinterned along with the remains of 14 others left in the ground. A principal complaint of the Oversight Committee was that the southwest section of the Oaklawn Cemetery had been exposed to water currents over the many years and was now beneath the water table. Chairman Ross described it as a “mud pit.”

The Oversight Committee and some of the archeological team called for further study to possibly rebury the 19 at a different site at Oaklawn above the water table.

However, the city forged ahead, reburying them on July 30, 2021.

FEATURED IMAGE

Oaklawn Cemetary’s reburial of mass graves after the City of Tulsa’s decision to not continue research of the area.